Drought and record hay prices wreak havoc on producers | Current edition

[ad_1]

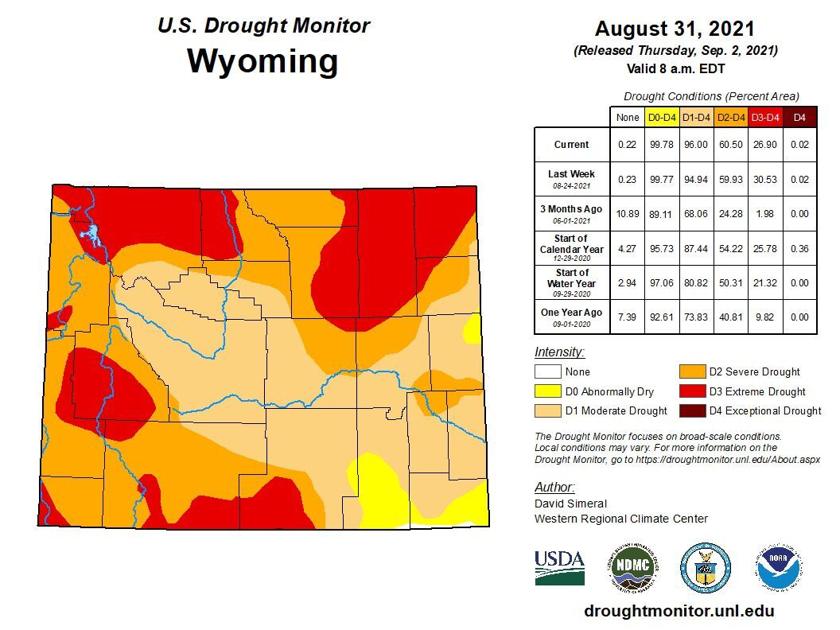

In an industry already ravaged by the fallout from the pandemic, agricultural producers in Wyoming are now grappling with Mother Nature as much of the state and the West is in the throes of severe drought. Lack of moisture, coupled with parched pastures and rangeland conditions, has led to record hay prices as many herders face the difficult choice of reforming herds and selling calves early.

As of May, the United States Department of Agriculture designated most of Wyoming counties as major natural disaster areas, with moderate to severe drought, particularly in the northeast and northwest corners of the state, as well as in the southern and southeastern counties.

The most recent USDA Crop Survey released on August 8 rated Wyoming’s pasture and range conditions as 67% very poor to poor, compared with 8% for good or excellent. Likewise, topsoil moisture conditions fell largely in the very short to short moisture category at 72%, compared to 28% of pastures or rangelands with adequate or excess moisture.

“This year is one of the worst drought years I have seen in 65 years,†said Clyde Bayne. Bayne is a breeder from Northeast Wyoming and an insurance agent with the Mountain West Farm Bureau, based in Newcastle.

Crop insurance is a means of mitigating losses caused by drought and other weather hazards, which is only made affordable because it is heavily subsidized by the federal government, which covers about 60% of the crop. premium of the breeder or the farmer. Crop insurance is overseen by the Federal Crop Insurance Program and administered by the Risk Management Agency, with policies sold and managed by private sector insurance companies.

In 2020, 7.3 million acres in Wyoming were insured for more than $ 171 million in protection, according to National Crop Insurance Services. Among the insured, farmers in Wyoming paid $ 10.6 million for coverage, with more than $ 30 million paid by insurers to cover losses and an additional $ 24.6 million for liability protection. cultures. According to the same figures, Wyoming’s crops contribute $ 1.5 billion to the economy.

The bonuses are based on a 20-year average of loss costs, according to Laurie Langstraat, vice president of public relations at NCIS, who said the formula varies widely across crops, regions and commodity prices, and that a bad year is not necessarily going to have a huge impact on a producer’s premium.

In July, the RMA authorized emergency growers to streamline and speed up compensation payments to crop insurance policyholders in drought-stricken areas of Wyoming and the United States.

Policies come in all shapes and sizes and cover over 100 different crop types, as well as livestock, ranges, equipment, and a variety of coverages ranging from 40% to 75%, as well as other variables to protect loss margins, Bayne mentioned.

“It is the most dangerous product to market in the insurance industry,†Bayne said. “The government gives you a deadline to meet, and you have to be specific. “

Another huge problem with the industry itself, Bayne said, is the lack of RMA drought measurement points in the state, which are typically located near tributary systems, and therefore are not representative of the various ecosystems in all counties of Wyoming. Because these measuring points are used by the agency to measure drought, the calculations do not accurately interpret what is actually happening on the ground.

This is true not only in Wyoming, but in the Dakotas and eastern Montana. He said he had reported it to RMA for the past 20 years, and while they agree with his assessment, they nevertheless did nothing to correct it.

“For a grazing and forage program to work effectively,†he said, “they need to have enough points to correctly interpret the conditions.â€

Despite their imperfections, these insurance programs have helped Wyoming farm producers stay in business.

This year, Bayne said they have heard from more producers than ever before, including those who have never had coverage. The bulk of its customers in the northeastern state are on forage or pasture land, with most, if not all, having filed claims this year after record cuts and hay prices through the roof going from $ 250 to $ 350 per person. tonne.

“Most of the Wyoming producers struggled,†he said. “I have never seen hay so expensive, and people have to go further and further to buy it.”

Hay has been the hardest hit of any Wyoming crop, according to Rhonda Brandt, state statistician for the USDA; it is also the state’s largest crop at around 1 million acres, including alfalfa and other varieties. Winter wheat is the state’s second largest crop at around 120,000 to 140,000 acres, followed by corn which ranges from 80,000 to 100,000 acres, Brandt said.

In terms of production, as of August 30, only 50% of all alfalfa was of good to excellent quality, the name used to determine prices, compared to a five-year average of 75% for the same period and 60% for the last time. year.

In contrast, corn is doing exceptionally well this year, especially for producers in irrigated pastures in the southeast who have not been so badly affected by drought conditions in other parts of the state. .

According to the USDA Crop Progress Report for the last week of August, corn production was around 93% for the highest quality product, compared to a five-year average of 79% .

Corn has also benefited from less hail and wind damage this year, Brandt added, as well as less disease.

“Corn is on a cruise,” she said. “It’s going a lot better this year, unlike some other cultures. “

Perhaps the only benefit stemming from the drought is that the designation grants producers eligibility for a variety of assistance programs administered by the USDA Farm Services Administration that provide emergency credits and loans up to $ 500,000 for various salvage needs, from recovery of losses to replacement of equipment or livestock.

There are a number of drought relief programs, according to Andrea Bryce, program specialist at Wyoming FSA, from funds set aside through the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program, designed to help producers affected by COVID- 19. Eligible producers were allowed to request payments of up to $ 500,000, depending on annual returns, number of shareholders and number of head of cattle. In 2020, COFOG disbursed just under $ 186 million in two installments to agricultural producers in the 23 counties that do not have to be repaid, with the next 2021 funding application deadline set to be set in mid -October.

Other federal disaster assistance programs, such as the Livestock Forage Disaster Program and the Non-insured Crop Disaster Assistance Program, among others, have also been disbursed, totaling just under $ 54 million. dollars to date, with a planned amount of $ 50 million to be disbursed this year.

The majority of these programs are directly tied to the USDA Drought Monitor, Bryce noted, as the state experiences its second year of drought. Farmers on irrigated land have done much better, with most of the programs designed to help dry farmers and producers on non-irrigated land.

“The markets have been really hit by the pandemic,†said Bryce, noting that in his 20 years of work this has been by far the busiest year. “When the supply chain broke, it really took a toll. And now the drought.

Nonetheless, she said she heard all the time how good the hay was in Wyoming when she traveled and that she wasn’t put off by a few rough years.

“It is an excellent state in terms of agriculture,” she said.

The impact on a grower varies wildly depending on their location in the state, said Brett Moline, director of public and government affairs for the Wyoming Farm Bureau Federation.

“Irrigated farmers are doing very well,†he said. “Corn really likes hot weather, and if you have water you are in good shape.

Dryland farmers, however, have been really hit hard this year. Moline cited his brother’s ranch in Aladdin, where he produced only about 10% of his hay crop due to hot weather and parched pastures.

This, coupled with the high price of hay, prompts many ranchers to slaughter their herds and sell calves 50 to 75 pounds less. In addition to lower profit margins, despite relatively decent calf prices, most ranchers will not get their money back, and it may take years to rebuild their herds, Moline said.

Another year of drought is going to wreak havoc on the agriculture industry again, he said, but then again, he is optimistic about the opportunities to help the industry by increasing the number of processors in the state and finding more markets to export Wyoming beef and other products.

Either way, Moline said, the biggest problem is that the industry is dependent on the weather, over which it has no control.

“Agriculture has always been a low-margin industry,†he said, “and always will be. “

Bayne argued the impact the two-year drought had on pastoralists, noting that those who have made the most of bank loans may not be able to survive.

Conversely, Bayne, who has been involved in both breeding and selling insurance for more than three decades, is hardly discouraged by bleak short-term forecasts.

“We are among the most optimistic people in the country,†he said. “We take the biggest risks and we love what we do. “

[ad_2]